saying goodbye to poor

sabu

by Douglas Messerli

Ian Iqbal Rashid (writer and director) Surviving

Sabu / 1997

The Mysore Indian-born actor Sabu (born Selar

Sabu in 1924, also known as Sabu Dastagir) was a beautiful child star whose

career began at the age of 13 when he was discovered by director Robert

Flaherty and cast as Rudyard Kipling’s Toomai in Elephant Boy, directed

by Flaherty and Alexander Korda, the latter of whom would also direct Sabu in The

Drum (1938) and the hit movie The Thief of Bagdad (1940) when the

boy was 16 years of age. Roles in Korda’s Jungle Boy, another

Kipling-inspired film, and John Rawlins’ Arabian Nights, both from 1942

followed, locking him into career as a figure in works of high exoticism,

which, after World War II would result in his performance mostly in grade B

movies, both British and American, for the rest of his life.

At

the age of 20 Sabu became a United States citizen and served in the Army Air

Force as a tail gunner and ball turret gunner on B-24 Liberators.

In 1947 he performed, at age 23, in what his last and greatest

high-quality film as the Young General Dilip Rai in what was perhaps the most

exotic and erotic film of them all, The Black Narcissus, directed by Korda’s own “discovery,” British filmmaker Michael

Powell, who described Sabu as having a “wonderful grace” about him.

A

year later Sabu married Marilyn Cooper whom he met on the set of Song of

India. They had a son, Paul, who later established the band Only Child

which created big hits for David Bowie, Alice Cooper, Madonna, Prince, and many

others (“Cassie’s Song,” “Just for the Moment,” “New Girl in Town,” etc.)

Sabu’s career opportunities, once the beautiful boy he came of age, had

mostly evaporated. In 1950 a fire to the second story of his family home in

Hollywood was tried as a case of arson, but may have actually been arranged by

Sabu himself in order to receive insurance money which he needed to help his

family financially survive. He died, at age 39, of a heart attack, only two

days after a checkup with a doctor who reportedly had told him: "If all my

patients were as healthy as you, I would be out of a job.”

Ian Iqbal Rashid’s remarkable short fictional documentary of 1997 begins

with an Indian man relating the early cinema days of the legendary child actor

Sabu in what his son will soon describe, interrupting the narration, as a

“Prince of Wales” voice. We catch quick glimpses of Sabu performing in Elephant

Boy and The Thief of Bagdad.

Suddenly the film shifts to black-and-white, where we see the

British-sounding man’s son smoking a cigarette on the street and seeing his

father (Suresh Oberoi) walking toward their house, calls out to his him, the

father refusing to respond. Inside the walls and shelves are lined with

photographs of the young Sabu, a copy of Life with Sabu on the cover,

perhaps of the time of Sabu’s marriage, etc. The color “documentary” continues,

while we witness more clips from Sabu’s films:

Sabu found fame and

fortune in Hollywood. Still only as a

teenager, Sabu was

living the life that most immigrants to

the West could only

dream of. When my son was a boy I’d

make him watch Sabu’s

films on television. I’d allow him to

stay up late. It was

important he should know we can succeed

in the countries. That

it’s possible.

As

his son Amin (Navin Chowdhry, playing the director), asks his father to now

talk a little more about his coming to England and what life was like, we

realize that this is not a documentary about Sabu but rather about the young

director and his father, whose values we soon discover are quite in opposition

to each other.

In

the kitchen, soon after or at another time (again filmed in black-and-white) we

see the father preparing a full Indian dinner, the son, having brought him a

tape of Indian music with jazz infusions, the father responding, “Fusion or

confusion.” Asked if he is staying for dinner, Amin responds he’s got an

appointment with his psychiatrist. He’s stressed. Besides, the son soon reminds

his elder that he doesn’t eat wheat, dairy, meat. “All the things you said were

good for us when I was a kid, they’re not.” We notice he’s wearing a T-shirt

which sports the words “Gay and Lesbian Center,” something which obviously has

stressed his Muslim father as well.

Again through a color-film sequence, we see the son recounting his

father’s experiences of having come to England to be a policeman, but after

being refused year after year worked as a security guard, proud of what he

does, proud of being loyal.

At

another meeting in the kitchen, where the father is fixing dinner, Amin

announces that he needs to talk to his father about something, the elder

responding, “You’ve decided to meet a nice Muslim girl and give us all a reason

to live?” The son has shown the movie to some “important people” who are

interested if only they can finish it. Yet his father finally responds that he

doesn’t think he should be making a film about Sabu. “You are not worthy.

...You’re making fun of a great Hollywood star.”

The son’s response says nearly everything that represents their vastly

different conceptions of the world which they cohabit: “Hollywood star! He was

a colonialist fantasy. Those films dad, they look at Sabu with a colonizers

gaze.”

“Why make a film” his father protests, “about someone you despise?”

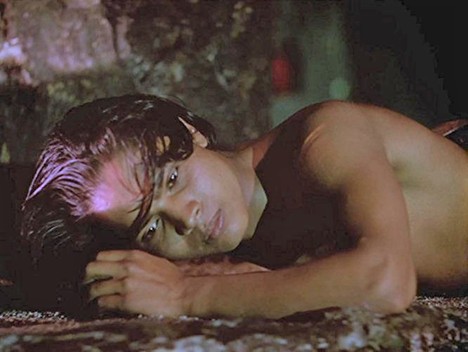

When we return to the description of Sabu, his golden almost nude body

spread out in the sand we might almost

imagine that the narrator was speaking to us from the pages of a gay physique

magazine rather than the father’s front room:

Sabu had an unnatural

natural beauty. Such a beautiful body.

A muscular athletic

physique. [In the clip, Subu turns over

to reveal the front of his

body] I told my son, look at Sabu’s

body, that he should

exercise and himself look like Sabu. But

he was always reading his

books and playing with his dolls

and singing songs. Never

interested in exercise.

Clearly if, as the son argues, Sabu was seen

through the colonizer’s gaze, so also has his father and others seen him

through a queer gaze.

Again back in the kitchen (in black and white) the son continues: “You

know the way you talk about him...it’s almost like.... Those movies filmed him

like he was a woman. And you bought into it!”

The resultant anger ends in the father hurling back his own insults at

his son’s admiration of white boys.

At another moment during the filming, in which the father has

momentarily escaped to the backyard, they talk about Sabu’s death. “Poor Sabu.

Died so young,” the father looking over at his son smoking a cigarette,

“probably smoked. Anyway he wasn’t a Muslim.”

Amin responds: “I don’t think it was smoking. I think he was probably

crushed by a film industry that rejected him when he became an adult. He

couldn’t get any decent work. Gave up hope.

....It was about racism dad, a Paki leading man kissing a white woman on

the screen. It was never going to happen.”

The father finally at his wit’s end, storms out. “When I get back I want

all of you out of my house.”

In Rashid’s film, we have come to perceive, Sabu is but a symbol of all

that one generation perceives as a continuation of the racism and denigration

of outsiders about a culture that the previous generation could not admit if

they were to survive and succeed to the best of their abilities. In this short

film we see not just the generations clashing against their different

perceptions about moral values, work ethics, and sexuality, but facing off in a

directional shift in the entire course of history: for Amin’s father every

patient step on his part was a movement forward, a small act of progress that

could lead ultimately to assimilation, while for Amin everything is turned

around, having never resulted in significant change; the hope to which his

parents’ generation had been committed has shifted into a despair for what Amin

and his friends see as movements into the past of discrimination and outright

hate for anything that stands outside of ruling society’s normative cultural

patterns. The two of them view the world from entirely different perspectives.

Yet, in this director’s amazing short work, father and son each are able

to turn around and see one another from the other’s viewpoint, which brings

them back to life, away from their frozen stares into the future and past, into

the present:

Amin’s father speaks: “When he was growing up, I tried not to talk to

him much about the past, about back home. I thought I should focus on the

future, tell him what he didn’t know about this place. Instead he told me.”

In antiphon Amin speaks: “He left Uganda* with no money. He started from

scratch. He rebuilt his life. He had courage. How did he do it? It couldn’t

just have been so his son might have a better life. It just couldn’t.”

The father realizes now that when Peter Sellars and other actors rubbed

a chocolate-covered makeup across their face, everyone laughed. “They were

laughing at me.”

Amin speaks of the time when he first told his father that he was gay,

recalling the look upon his face, realizing, “He’d have swapped me for anyone.

Anyone else’s son.”

And the night he told us he was gay, his father recalls, he stayed over

that night, wanting everything to be all right: “That took courage.”

Returning to the house, Amin finds his father watching a Sabu film and

joins him on the couch, the two quoting in unison a line about Mogli from

Sabu’s Jungle Boy. The elder agrees to finish the last few frames of his

son’s film with him, remarking that he will be all right with whatever his

director son presents in this movie. His philosophy he says is “Relax, it’s

only a film. What harm can a film do?” If his question appears to offer a true

reconciliation, it also belies the truth that language, story, and image are

the most terrifyingly powerful things in life.

*Director Ian Iqbal Rashid was born in Tanzania, from

where his family, after being refused asylum in the United Kingdom and the US,

settled in Canada, Rashid finally moving to London as an adult. Rashid has made

other films, including the gay comedy Touch of Pink, but is best known

in England for his poetry.

Los Angeles, January 2, 2021

Reprinted from My Queer Cinema and World

Cinema Review (January 2021).