dirty heroes: body and soul

by Douglas Messerli

Antonio Capuano

(screenwriter and director) Pianese Nunio, 14 anni a Maggio (Sacred

Silence) / 1996

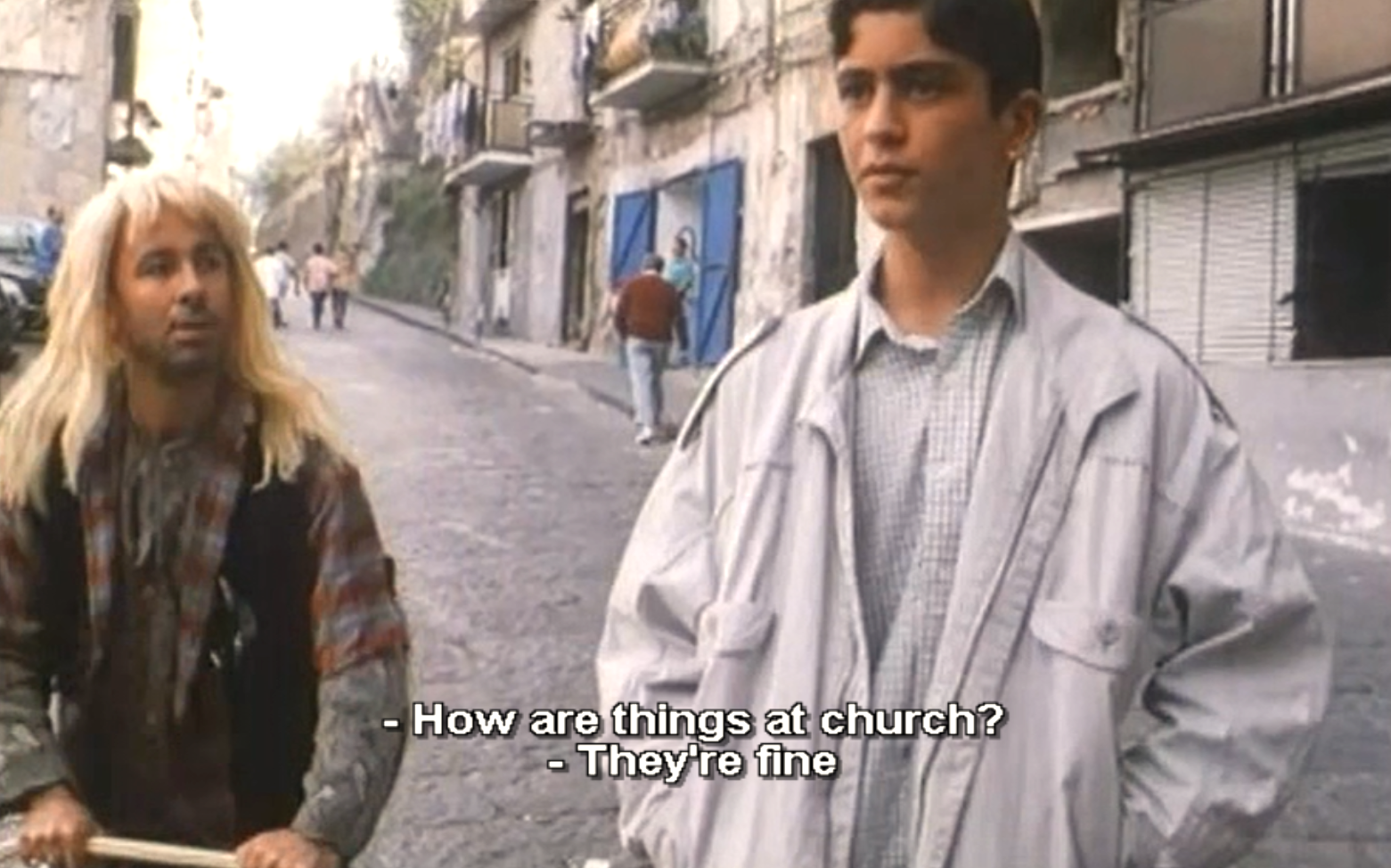

The local Naples priest, Don Lorenzo Borrelli (Fabrizio Bentivoglio), titled the blue jeans priest, is akin to the heroes of many a movie, including those represented in Matteo Garrone’s Gommorah and in the character of Father Pete Barry in Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954). Both characters Barry and Borrelli along with director Garrone are fighting war, so to speak, against the local mafia or in the Naples more particularly the Camorra, who controls Naples and is prevalent in Borrelli’s poor neighborhood. And Borrelli knows that he cannot save the young children he attempts to nurture as long as the parents accept the mafia and engage with them as a daily part of their lives.

Yet Borrelli has a serious flaw: he has

uncovered a beautiful young 13-year-old, a talented singer who also plays the

organ for his church, and himself wishes to become a priest, with whom he has

he now spends his meals, his intellectual tutelage and, rather shockingly, his

“personal affection.” In short, this hero-priest is also pedophile, trapped

between his ideals and his body.

The local mobsters, tired of the harangues

against them and, for all their seeming strength, necessarily seeing the

revealment of the priest’s secret life as their way to shut him up, begin their

pressure on the young acolyte.

In a perhaps overlong series of events and

a great many verbal attacks against his social enemy, the Camorra, the movie

makes it way surely to where we all know it must end.

Director Capuano does not forgive his

tragic hero for his awful sins of the flesh, but does reveal him in the final

scenes as a kind of Christ, who refuses even a funereal in the church for one

of the Camorra leaders who has just been killed.

By film’s end, disgusted as we may be by

his sexual behavior, the viewers themselves must ponder the same question.

By the time of his last visit to Borrelli,

the priest even permits the young boy to betray him to the police with the

words, “If you report me, I’ll say nothing against you.”

The boy does so, almost unwillingly, yet

tired, as he puts it, of being a “sheep.” And the result is the silencing of one

of the few social forces attempting to stand up to the Camorra.

We recognize that even Nunio’s life will

end disastrously, as in one professional gig he ends up with another boy

singing in the subways.

This movie could not probably me made or

taken seriously today when instead of pondering such issues we simply dismiss

them as immoral, but in 1996, Matt Blake writing in The

Wild Eye, described it as “an amazingly courageous film,

considering the fact that it’s essentially about a paedophile and, what’s more,

a paedophile who is in many other ways so upstanding and heroic. Lorenzo

certainly makes for a difficult protagonist, at the same part admirable and

despicable; and the fact is that he takes advantage of a vulnerable young man

in much the same way as the Camorra he so despises. But he’s a genuinely tragic

protagonist, someone who tries to do good but fails because of fatal character

flaw which not only undermines his cause but also his whole moral bearing.”

This is the kind of film that one carries

with one for months after seeing it, a work gnawing at the heart and mind.

There is no easy answer for dirty heroes.

Los

Angeles, June 3, 2025

Reprinted from My Queer Cinema blog

(June 2025).