the vulgarians at the gate

by Douglas Messerli

Manuel Seff and James Seymour (writers, based on a story by

Robert Lord and Peter Milne [uncredited]), Lloyd Bacon (director), Busby

Berkeley (dance numbers) Footlight

Parade / 1933

By

coincidence, the same week in July when Howard and I attended a local large

screen showing of James Cagney’s Yankee

Doodle Dandy, Netflix sent me a DVD of Cagney’s 1933 film, Footlight Parade, enabling me to see

Cagney as a hoofer twice. He got far more screen time and far better dances in Yankee, but as an actor Cagney is more

energetic and far more frenetic in Footlight;

when the camera’s on him, there’s hardly a moment when the former Broadway

director, Chester Kent, isn’t cooking up a new dance, booking a new movie house

for his “musical prologues,” interviewing a new cast member, or simply

strutting from room to room wherein his mini-factory of rehearsal halls he

tries out numerous numbers (both musical and human) simultaneously.

Battered equally by his producer’s wife,

Harriet Bowers Gould (Ruth Donnelly), who troops in an army of would-be

protégés (including Dick Powell as Scotty Blair), and the same producer’s

nay-saying brother, Charlie Bowers (Hugh Herbert), who would like to censor

every act that Kent cooks up, Kent is caught up in a near whirlwind of

moment-to-moment changes. The movie, filmed just before the establishment of

the Film Production Code, joyfully makes fun of what clearly the writers and

directors saw coming, as Bowers demands the dolls—toy dolls, not the real

girls—sport brassieres ("...uh uh, you know Connecticut.") at the

very same moment that Kent is transforming his scantily clad dancers into

yowling cats and the film’s director is dishing out a gay satire in which Dick

Powell sings of his love, arms about his cigar-munching musical director, a

stand-in for any would-be lover.

Fortunately, Kent has the level-headed and

seemingly unflappable, Nan Prescott (Joan Blondell) by his side, a secretary so

confident that the film suggests she could run the place, even if—given the

machinations of Kent’s former wife, Cynthia (Renee Whitney) and Nan’s gold

digger friend, Vivian Rich (Claire Dodd)—she can’t always be as sure of her

man. Fortunately, he’s too busy to spend much time but a lunch date with other

women.

Besides, he has

choruses of loving boys and girls at his at the flip of his wrist, and it’s

those lovelies that are truly the focus of this film; just to make sure,

plain-looking secretary, Bea Thorn (Ruby Keeler), who has secretly (even to

her) fallen in love with Scotty Blair, decides to marcel her hair and jump into

the larger pool.

Although the film was directed by the always sturdy Lloyd Bacon, the

dance and musical numbers, at the heart of this extremely light-hearted work,

came directly from the overheated imagination of Busby Berkeley, who in this

movie went all out in the work’s featured three “prologues,” “Honeymoon Hotel”

(Harry Warren, music and Al Dubin, lyrics), “Shanghai Lil” (by the same duo),

and “By a Waterfall” (by Sammy Fain, music and Irving Kahal, lyrics). As if the

numerous sexual innuendoes of the first song, performed supposedly on-stage in

a hotel-sized set, were not enough, Bacon links up the three numbers by busing

the girls from theater to theater, while we glimpse them openly changing

costumes.

Berkeley’s

“Shanghai Lil” gives Cagney a terpsichorean turn with Ruby Keeler impersonating

his Chinese prostitute girlfriend, much in the way that Gene Kelly courted Cyd

Charisse in Singing in the Rain.

But it is in “By a Waterfall,” with Dick

Powell croons out his love to Keeler that really gets the full Berkeley

treatment and presages his several later Ester Williams musicals. I could

hardly describe the scene better that does John Wakeman’s World Film Directors, Volume One.

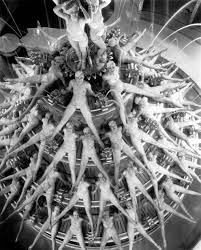

“The camera

then pulls back to reveal the waterfall itself

with Berkeley girls sliding down it like half-naked nymphs. retreating

still further to disclose an immense pool where the girls dive, swim, and float

to form geometric patterns that fold and unfold like flowers, separate and rejoin

in new shapes, and finally assemble themselves into a multitiered human

fountain from which water cascades into the pool.”

As critic Arthur Knight summarizes,

through the dance’s numerous fragmented shots, “It is the camera that is doing

the dancing, not the chorines!”

Strangely, by so

forcefully featuring these supposedly “on stage” elaborated numbers, Footlight Parade makes it clear why the

footlights of Broadway theater are no longer appealing. Instead of “real”

dancers, the camera is now both spectator and spectacle, an observer who in the

hands of someone like Berkeley, itself becomes the center of attention. Kent

can longer direct his Broadway works because the “vulgarians” are at the gate,

the talkies representing a kind of second-hand theatrics that speak in the

language of technology instead of true singing and dancing human voice and

bodies. Human beings have been collectivized to become the troops of war—a war,

in this case, against the live actors featured on the stage.

It’s strange

that this and other Berkeley movies so clearly made it apparent that motion

pictures were not what they pretended to be. Yet can any one of us easily turn

our gazes away from such cinematic feats?

Los Angeles,

July 11, 2017

Reprinted from World

Cinema Review (July 2017).