dream and language

by Douglas Messerli

Jules Massenet (composer), Henri Cain (libretto, based on the story by Charles Perreault), Laurent Pelly (stage director), Gary Halvorson (film director) Cendrillon / 2018 [Metropolitan Opera HD-live production]

Jules Massenet’s 1899 Cinderella-based opera, Cendrillon, was a bit hit upon its premiere at Paris’ Opéra-Comique; but only this year received a production for the first time at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Tastes changed early in the 20th century, and Massenet’s beautiful scores, with their tributes to everyone from Mendelsohn to Wagner, with a few stops for Mozart and Strauss along the way. But the fact that Cendrillon had never previously made it to Broadway seems to be a particularly sad event.

Fortunately, the great American mezzo-soprano, Joyce DiDonato rediscovered the work (after it had performed by Frederica von Stade) more than a decade ago and warmed up to it playing in a Laurent Pelly production (he also designed the remarkable costumes) in Santa Fe, London, Brussels, and elsewhere. As a regular in MET productions, it was perhaps inevitable that eventually DiDonato would be featured in a production in New York, and we can now hope that, given its great success, it may join the MET repertoire. Certainly, it was visionary of the MET to include it their famed live HD series, which my husband Howard and I saw yesterday in a Los Angeles movie theater, and which may help make it a production which audiences will embrace. Clearly, the elderly audience with whom we saw it loved the production, and I think their grandchildren might equally enjoy it.

Like Cocteau’s Belle, Massenet’s Lucette (Cinderella’s real name in this version) basically accepts her life as a cleaning woman to the vain stepmother, Madame de la Haltière (the always wonderful Stephanie Blythe) and her almost-idiot like stepsisters, dressed in comical-like balloon-like dresses that evidently stand for the haute-couture of the day. In comparison, at least in the early scenes, Lucette looks like a peasant woman from a Verdi opera. And despite her hard life, she is deeply loved still by her weak-willed father, Pandolfe (Laurent Naouri) who, after his wife’s death, inexplicably chose this monstrous woman of what she claims is a royal background. It may be that his little farm in the forest was simply not successful enough to pay the rent. Now the man simply suffers for his horrible mistake, his daughter paying the punishment for the crime.

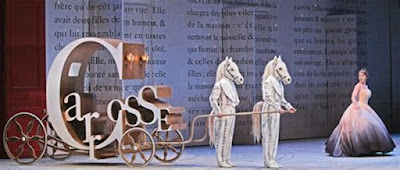

Most of Lucette’s life, when she isn’t busy cleaning up the storybook-like house—set designer Barbara de Limburg has covered the walls of the constantly shifting rooms with phrases from the Perreault tale—is spent sleeping and dreaming; and, in fact, she has a hard time, as we may as well, in knowing whether her experiences are real or simply dreams.

It is certainly a dream of an opera, with the soaring phrases of beauty, suddenly transforming into more comic passages, and moving back again into glorious romanticism, which conductor Bertrand de Billy described as “particularly French in style.

If this Massenet work is about the confusion of dream and reality—there are long periods when Lucette simply believes she has dream her entire visit to the ball and her later encounter with the Prince in the forest—this version, at least, is also all about hearing and language, the joy of being

Quite vindictively, it at first appears, The Fairy God Mother refuses to let the loving couple see one another in the forest, only allowing them to hear each other’s sad pleas. Yet that’s precisely the point. Hearing and reading reality is what truly matters here, not action and adventures. The only incredible actions in this work are Lucette’s flight from the ball at midnight, whereupon she loses her shoe, and the impossible attempts to find the foot that fits her glass slipper.

Otherwise, Cendrillon is a work of poetical and musical wonderment. Eventually, The Fairy Godmother comes to the rescue on a pile of large books. And Pelly’s and De Limburg’s direction and sets put their faith on spectral elements, allowing the Perreault tale to come alive in a way that Verdi or even the later Puccini, in their commitment to realism, might never have been able to imagine.

The opera closes suddenly, since we already know the end, with the chorus announcing that their tale has come to an end, the loveliest close to an opera that one might ever imagine, the char-woman in the Prince’s arms and even the terrible stepmother admitting—now that Lucette has found her own royalty—that she truly loves her. If we don’t believe her one little bit, it doesn’t matter. Cendrillon is a fairy-tale, a thing of language, as the host, Ailyn Pérez announced early on before the opera began, a much-needed tonic these days.

Los Angeles, April 29, 2018

Reprinted from USTheater, Opera, and Performance (April 2018).

No comments:

Post a Comment